“It ain’t Hollywood, my boy, it’s mescalito. In Los Angeles, it’s hard to tell if you’re dealing with the real true illusion or the false one.”

– Eve Babitz, Slow Days, Fast Company

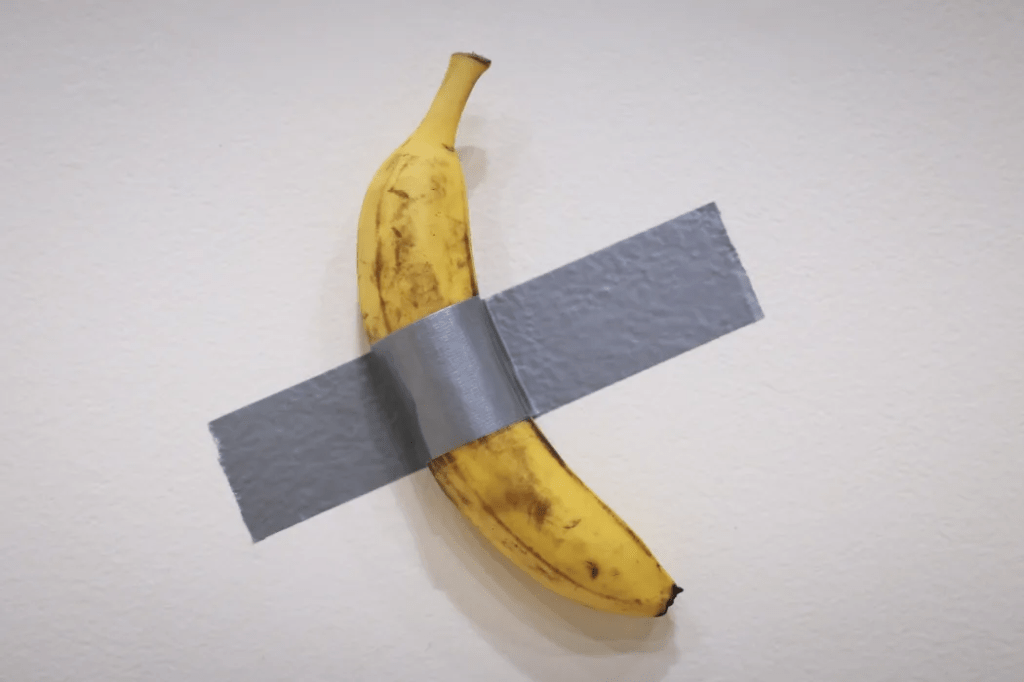

On a grey Manhattan sidewalk one November morning, Shah Alam stood beside his fruit stall in disbelief. The rush of the city hummed around him, its lights flashing like diamonds in the pools of rain against the tarmac. A partially-blind Bangladeshi immigrant, Shah works 12-hour days for just $12 an hour selling fresh produce to passersby. He had no idea that one such passerby was a Sotheby’s employee in a crisp suit. Perhaps he would never have handed over the barely ripe fruit in exchange for 53 cents if he’d known it would later be duct-taped to a wall and auctioned off for an eye-watering $6.2 million on the art market.

Created by Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan, the piece entitled “Comedian” debuted at the 2019 Art Basel fair in Miami, where it sold for $120,000. In November last year, it was bought by Justin Sun, a 34-year old cryptocurrency platform founder from China, for $6.2 million. Sun then preceded to, after handing over the exuberant amount of cash, further stun onlookers at a press conference in Hong Kong when he turned around, unstuck the slightly browning piece of fruit from the wall and began to chomp it down while laughing into the cameras.

Given that over 340 million people worldwide are experiencing severe food insecurity, going without food for an entire day or more, any reasonable person in the art world might stop and ask, “What the actual fuck are we doing in the name of ‘Art’?” But that didn’t seem to happen. Rather, it appears the big art players really do continue to live in their little White Cube, completely removed from the reality of the world. David Galperin, Head of Contemporary Art for the Americas at Sotheby’s responded with,“How do you value what, for me at least, is one of the most brilliant ideas in the history of conceptual art. And what better place to ask that question than in our salesroom, where tonight the answer came in at a resounding $6.2 million.” In a press release, Sotheby’s went further to call Cattelan’s works “revolutionary”, saying they “shared in a spirit of iconoclastic pranksterism that provoked audiences to question the meaning of art”.

Provoked audiences to question the meaning of art? Haven’t audiences been peddled with this question, over and over again in various different forms, since the early 20th century? How many times can this same “question” be marketed as “provocative” or “insightful” or “revolutionary”? Such questions were “revolutionary” back in 1917 (that’s 108 years ago..) when Andy Warhol parked his urinal upside down in the art gallery and called it Fountain. At the time, it certainly raised new questions about the social constructs of art, the collective stories we tell and believe about objects, and the meanings we project onto them to make sense of the world within our shared conceptual frameworks.

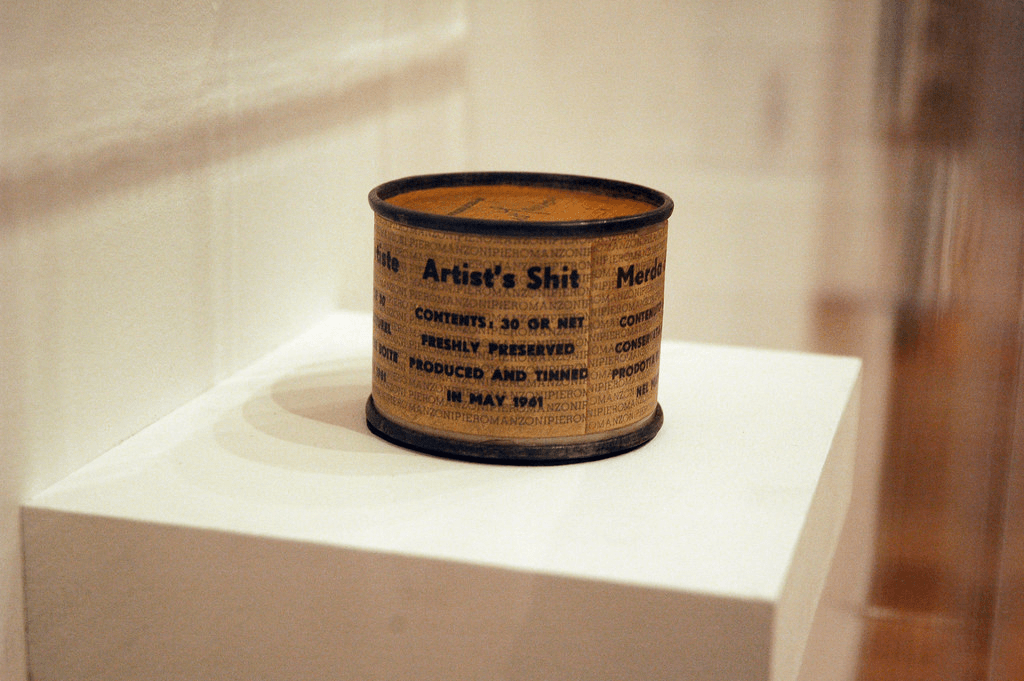

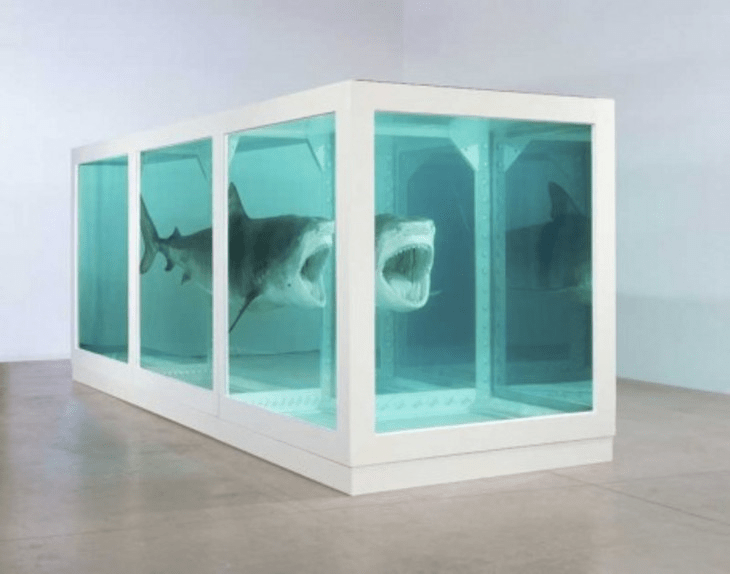

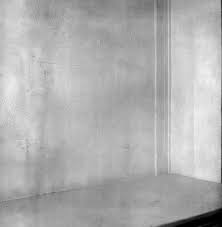

If you’re immersed in the “Art World,” peering through its self-referential lens, it’s easy to get swept up in pseudo-intellectual interpretations of this whole bananarama, as if afflicted by some collective amnesia. But this conceptual jesting has long passed its sell-by date, dripping down the white gallery walls like brown rotten banana pulp mush. Much of contemporary art seems to be stuck in a self-referential playback loop, on repeat, spinning past the likes of Piero Manzoni’s Artist’s shit in a can (exactly what it says on the tin), Damien Hirst’s The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (a shark suspended in formaldehyde) and Yves Klein’s The Void (an empty gallery space presented as an artwork). It’s refreshing to hear Chloé Cooper Jones, an associate professor at the Columbia University School of the Arts, say, “If Comedian is just a tool for understanding the insular, capitalist, art-collecting world, it’s not that interesting of an idea.”

What began, back in the early 20th century, as an interesting comment on art and its collective meaning has now grown into a direct and explicit expression of celebrity culture and wealth. Today, an artwork’s focal point—its value—is no longer rooted in its ideas or aesthetics but in the wealth it generates, the certificate of ownership passed from one hand to another. The ultimate commodity. It’s exactly as Sotheby’s David Galperin put it: “How do you value what, for me at least, is one of the most brilliant ideas in the history of conceptual art? And what better place to ask that question than in our salesroom, where tonight the answer came in at a resounding $6.2 million.” Back in 2019, when the art work sold for $120,000, Emmanuel Perrotin (art dealer and gallery owner) explained that securing a buyer for the piece completed the artwork. “A work like that,” he said, “if you don’t sell the work, it’s not a work of art.” The purpose of the artwork becomes to be sold on the market. How much clearer can it be? The value of the artwork lies solely in the cash it commands, its meaning reduced to a dollar sign.

If we step back, beyond the White Cube amnesia and self-referential loop, what does this absurd series of events—from a Manhattan fruit stall to a White Cube wall to Justin Sun’s bowels—really reveal? If we place it within the broader context of the world, outside the confines of those four white walls—where hollow questions posed by art professionals in black designer suits and wire-rimmed glasses about the meaning and value of art try to distract us from stacks of crisp dollar bills—what does it truly highlight in glaring, banana-yellow hues?

Again, Chloé Cooper Jones from Columbia University School of the Arts offers an insightful perspective: “It would be hard to come up with a better, simple symbol of global trade and all of its exploitations than the banana. If Comedian is about making people think about their moral complicity in the production of objects they take for granted, then it’s at least a more useful tool—or at least another direction to explore—in terms of the questions this work could be asking.”

I hope this work serves not to drag people further into the Art World’s meaningless, navel-gazing questions but instead pulls them out into the real world to confront the absurdity of their roles in upholding and perpetuating unjust systems. Systems that fuel wealth disparity, greed, hyper-materialism and consumerism, and environmental degradation —all for a privileged Global North audience that can afford to sit around debating the meaning of art at the expense of the Global South.